How to test a code that uses time? - Improve quality of your project, part I

Table of Contents

Java has amazing java.time package. There are few useful classes like LocalDateTime, ZonedDateTime, Instant or Clock. But do you know how to use them? If you are using untestable Instant.now() syntax - you probably should read this post.

Concepts you must understand

In the very first step, you must understand a few concepts that not everybody understood. If you know the theory, just skip to the section with code.

Below, I will try to explain why using always the LocalDateTime is not a good idea, and you most likely should use ZonedDateTime or Instant.

Timezones

Because the Earth is moving, rotating all the time, the noon is in only one place at a time. This means that in other places must be earlier or later.

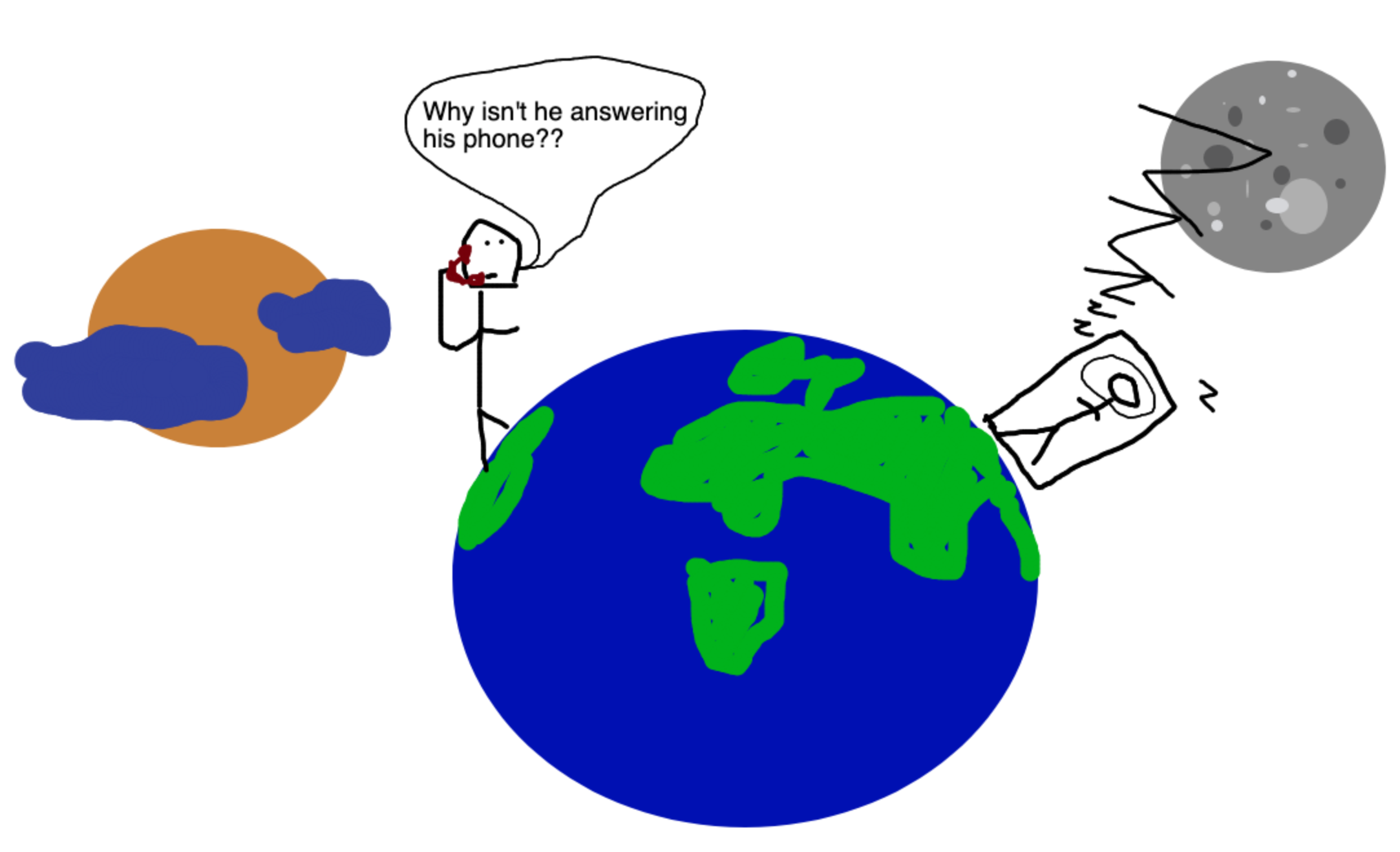

Imagine having a friend on the other side of the globe. You ask him to call you afternoon…

… but he doesn’t call and doesn’t answer his phone. Why?

You ask him to call at 5pm, but 5pm at his region will be in 10 hours, but in your region, in your country the 5pm is right now. What you see on your watch is called local time. And your friend, on the other hand, has different local time. This is a known and already solved issue. Some years ago, some smart guy divided the Earth into smaller regions called the time zones. If you and your friend are both in the same time zone, it means that the sun rises approximately at the same time in your and in his house.

You probably already known this and understand the concept perfectly. But when you are coding, you should consciously decide whether you need to operate on local time or on the time with a time zone.

Timestamp

2022-04-22T18:00:00.000Z is the really nice representation of the date, humans like it. However, your computer doesn’t. Machines prefer the numbers, one int > human-readable string. So, there is another representation of the date - timestamp. Timestamp is the point at the timeline.

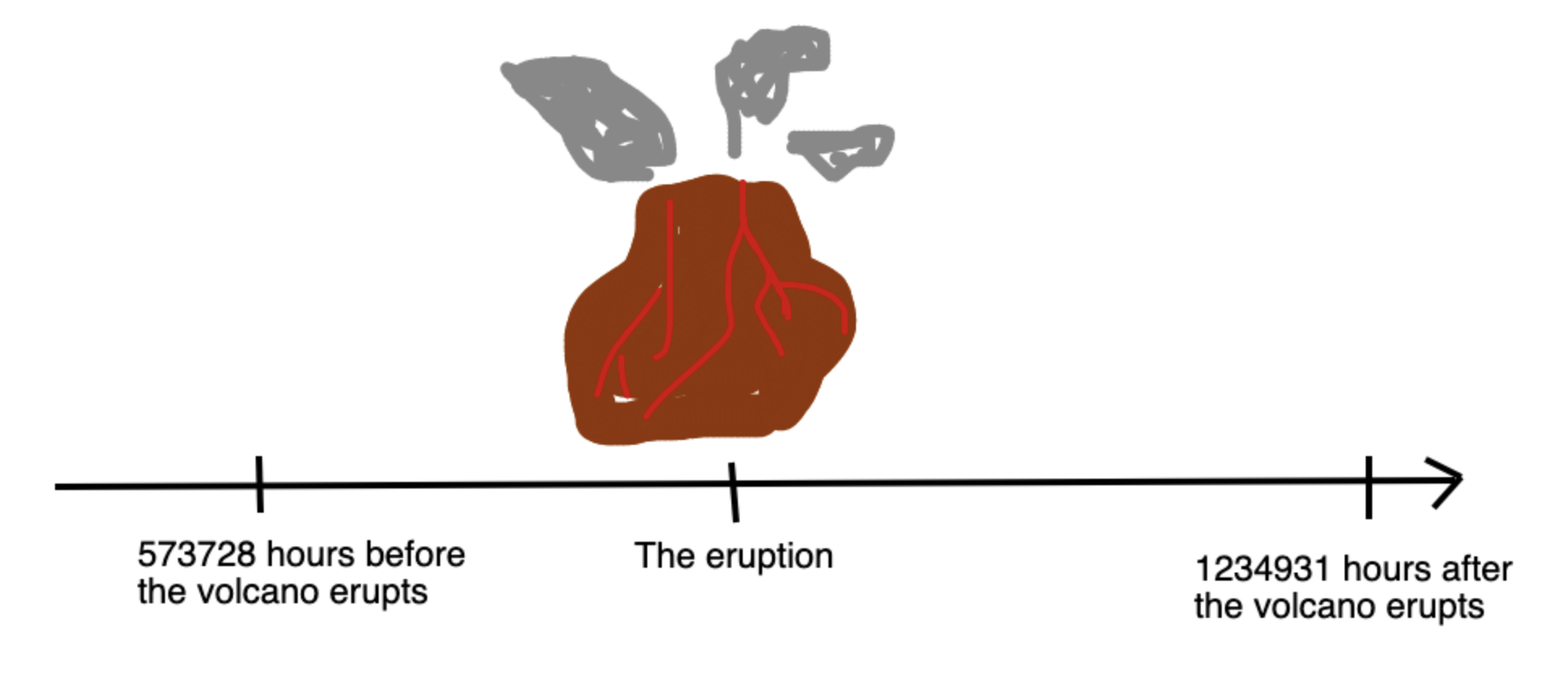

Imagine an eruption of a volcano. The volcano exploded at 8am PST time, it was 8pm at ALMT zone. In the space, in the ISS was 2pm. The clue is that the eruption is an event on the Earth timeline.

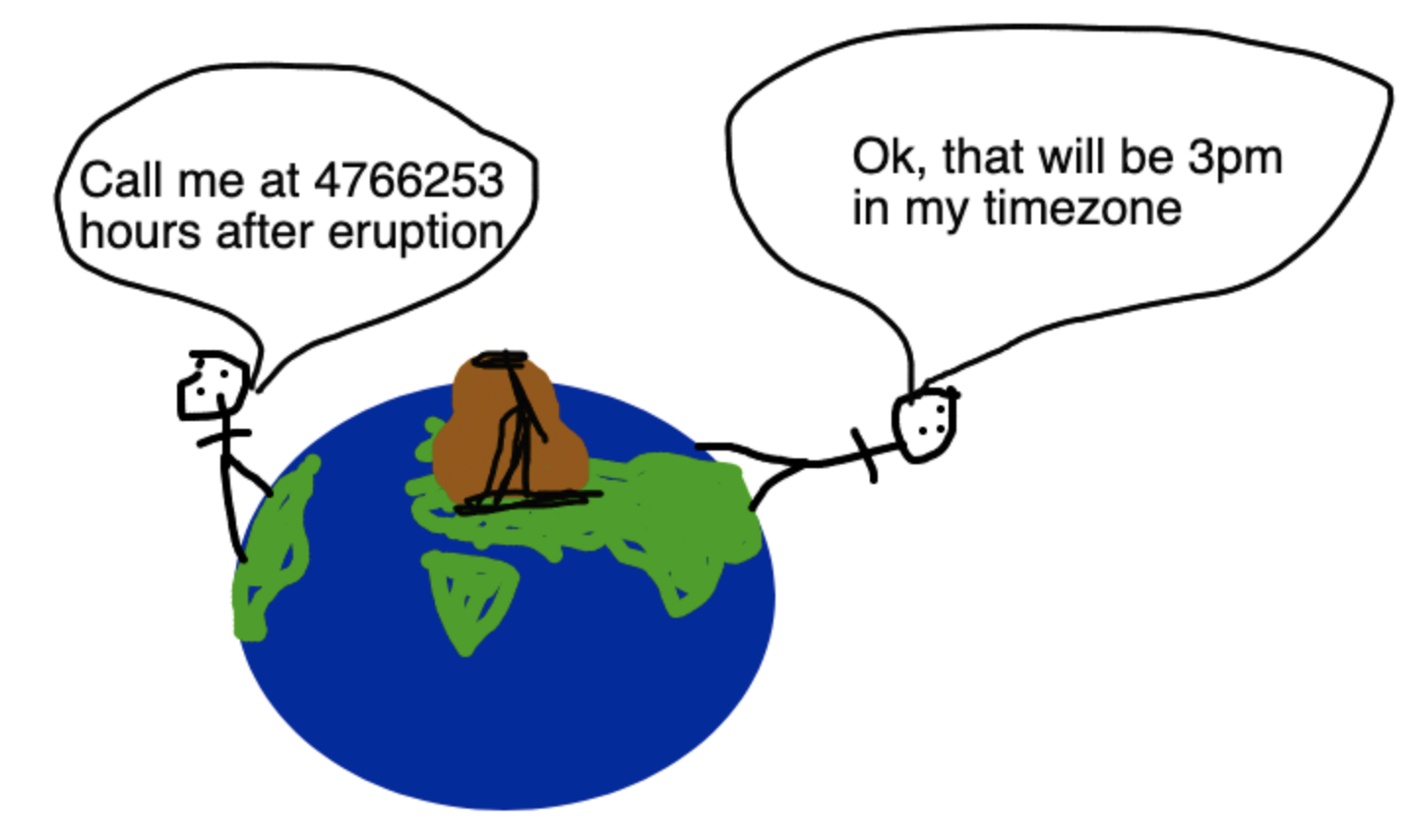

We can write a date referring to that event, as we do with years. You probably know the notation Before Christ or Current Era, 2022 BC/CE, similar concept.

Now you can schedule a meeting with your friend using this precise notation.

In computer since, the unix time is used commonly, the number of seconds (or milliseconds) that have elapsed since 1 January 1970, 00:00:00 UTC.

Timestamp vs local date

Short summary:

- Timestamp - describe the point in Earth timeline. Represented by

Instantclass. Time-zone independent. It’s like a pointer to the global timeline. - Local date - what you see on your watch. Represented by

LocalDateTime,LocalDate,LocalTime. - Date with timezone - time displayed on all watches in a some geographical area. Represented by

ZonedDateTimeandZoneIdclasses. It’s likeInstantwithZoneId.

It’s critical to choose the right type for the problem and not mindlessly, always use a LocalDateTime. If you want to read more - there is wonderful Java 8 Time - choosing the right object article and amazing StackOverflow answer.

Java has more useful classes like DayOfWeek or Duration, but we won’t focus on them.

Example, typical app

If you already know what representation of time you need, it’s time to code something. Let’s say you must create a piece of code that reset a user’s password. Simply generate a token and send via email. The token is valid for one hour. User has to use that token to set a new password. How can we achieve that?

public class ResetPasswordService {

private final ResetPasswordTokensRepository repository;

private final EmailSender emailSender;

public ResetPasswordService(

ResetPasswordTokensRepository repository,

EmailSender emailSender

) {

this.repository = repository;

this.emailSender = emailSender;

}

public void sendToken(UserId userId) {

var validTill = Instant.now().plus(48, HOURS);

var token = generateToken();

var tokenEntity = new TokenEntity(

userId,

token,

validTill

);

repository.save(tokenEntity);

emailSender.sendResetPassordEmail(userId, token);

}

private Token generateToken() {

return new Token("xyz");

}

public void resetPassword(UserId userId, Token token, Password newPass) {

var entity = repository.findByUserIdAndToken(userId, token)

.orElseThrow(TokenNotFoundException::new);

if (entity.validTill().isAfter(Instant.now())) {

throw new TokenExpiredException();

}

// rest password

}

}

This is a code you probably have seen many times in your career. In general, this code looks fine, but there are two lines we have to discuss.

var validTill = Instant.now().plus(48, HOURS);

It means that the token is valid for 48 hours from now.

if (entity.validTill().isAfter(Instant.now())) {

Here we are checking if the token is still valid.

Can we test these two methods? We can, but no easy, not fully and dirty.

@Test

void should_generate_token() {

var service = new ResetPasswordService(testRepository, mockedEmailSender);

service.sendToken(testUserId);

assertThat(mockedEmailSender.lastRestPasswordEmail())

.hasToken("xyz")

.isInTheFuture();

}

During the test, we’ve generated the token and verified the email that was sent to a user. We can assert the token, but we cannot assert the validity time. I mean, we can check if it’s not null and if it is in the future, but there is no easy way to assert the value. The value should be Instant.now().minus(few, MILLISECONDS), but we don’t know the exact value, only approximately, with few milliseconds’ epsilon.

Maybe we can unit test the restPassword method? Let’s see what we can do.

@Test

void should_throw_exception_when_token_is_expired() {

var newPass = new Password("some-password-123$%^");

var token = new Token("xyz");

var tokenEntity = new TokenEntity(

userId,

token,

Instant.now().minus(100, DAYS)

);

testRepository.save(tokenEntity);

// and

var service = new ResetPasswordService(testRepository, mockedEmailSender);

assertThrown(TokenExpiredException::class, () -> service.resetPassword(userId, token, newPass));

}

@Test

void should_reset_password_when_token_is_valid() {

var newPass = new Password("some-password-123$%^");

var token = new Token("xyz");

var tokenEntity = new TokenEntity(

userId,

token,

Instant.now().minus(1, HOURS)

);

testRepository.save(tokenEntity);

// and

var service = new ResetPasswordService(testRepository, mockedEmailSender);

service.resetPassword(userId, token, newPass);

assertThat(userId)

.hasPassword(newPass);

}

As you can see, we can test the resetPassword method. But are these test goods? As you can see, we have to insert entities directly to the database. Also, we have to simulate the time when the token was generated. Unit tests should not insert any data to the repository, we can do it better.

Clock

Java has the Clock class. For the first time this class seems to be useless, calling the clock.instant() gives you the same result as Instant.now(), but Clock has no static method, and you have to inject an additional bean. Looks like overkill, but the advantage is that we can inject different implementation during the tests. Try to add the Clock to our service class.

public static class ResetPasswordService {

private final ResetPasswordTokensRepository repository;

private final EmailSender emailSender;

private final Clock clock;

public ResetPasswordService(

ResetPasswordTokensRepository repository,

EmailSender emailSender,

Clock clock

) {

this.repository = repository;

this.emailSender = emailSender;

this.clock = clock;

}

public void sendToken(UserId userId) {

var validTill = clock.instant().plus(48, HOURS);

// send token

}

public void resetPassword(UserId userId, Token token, Password newPass) {

var entity = repository.findByUserIdAndToken(userId, token)

.orElseThrow(TokenNotFoundException::new);

if (entity.validTill().isAfter(clock.instant())) {

throw new TokenExpiredException();

}

// rest password

}

// ....

}

So, we have added a new dependency. But the app won’t run, there is no Clock bean. However, it’s easy to add it

@Configuration

class ClockConfiguration {

private static final ZoneId TIME_ZONE = ZoneId.of("UTC");

@Bean

Clock clock() {

return Clock.system(TIME_ZONE);

}

}

There is one thing to explain

clock.system(TIME_ZONE)

It’s the implementation of the clock that return the time from the system clock. We have to provide some time zone, the zone is used to convert the instant to zoned date-time.

@Test

void should_generate_token() {

var today = Instant.parse("2022-04-22T18:00:00.000Z");

var testClock = Clock.fixed(today, ZoneId.of("UTC"));

var service = new ResetPasswordService(testRepository, mockedEmailSende, testClock);

service.sendToken(testUserId);

assertThat(mockedEmailSender.lastRestPasswordEmail())

.hasToken("xyz")

.isValidTill(Instant.parse("2022-04-23T18:00:00.000Z"));

}

But there is still a problem with the resetPassword method, we still must insert the token manually. What can we do to resolve that issue and create the perfect test?

Custom time provider

We can create another interface, very similar to the Clock (or use InstantSource added with Java 17)

public interface TimeProvider {

Instant instant();

}

Next, replace usage of Clock with our TimeProvider

public static class ResetPasswordService {

private final ResetPasswordTokensRepository repository;

private final EmailSender emailSender;

private final TimeProvider timeProvider;

public ResetPasswordService(

ResetPasswordTokensRepository repository,

EmailSender emailSender,

TimeProvider timeProvider

) {

this.repository = repository;

this.emailSender = emailSender;

this.timeProvider = timeProvider;

}

public void sendToken(UserId userId) {

var validTill = timeProvider.instant().plus(48, HOURS);

// ..

}

public void resetPassword(UserId userId, Token token, Password newPass) {

// ...

if (entity.validTill().isAfter(timeProvider.instant())) {

throw new TokenExpiredException();

}

// ...

}

}

Finally, create implementation and register a bean

@Configuration

class ClockConfiguration {

@Bean

Clock clock() {

return Clock.system(TIME_ZONE);

}

@Bean

TimeProvider timeProvider(Clock clock) {

return new ProductionTimeProvider(clock);

}

@RequiredArgsConstructor

static class ProductionTimeProvider implements TimeProvider {

private final Clock clock;

@Override

public Instant instant() {

return clock.instant();

}

}

}

You may think this is all pointless, the TimeProvider interface boils down to Instant.now() call. It may look overcomplicated, but wait for second, test’s implementation.

public class TestTimeProvider implements TimeProvider {

private Clock clock;

public TestTimeProvider() {

this(Instant.parse("2022-04-22T18:00:00.000Z"));

}

public TestTimeProvider(Instant initInstant) {

this.clock = buildClock(initInstant);

}

@Override

public Instant instant() {

return clock.instant();

}

public void elapse(TemporalAmount temporalAmount) {

clock = buildClock(instant().plus(temporalAmount));

}

public void elapse(long amountToAdd, TemporalUnit unit) {

clock = buildClock(instant().plus(amountToAdd, unit));

}

private Clock buildClock(Instant instant) {

return Clock.fixed(instant, ZoneId.of("UTC"));

}

}

And if you have integration tests, just register new, test’s bean

@Configuration

static class TestBeans {

@Bean

@Primary

TestTimeProvider testTimeProvider() {

return new TestTimeProvider();

}

}

I hope it starts to make sense. We’ve created the class that allows us to time travel during the tests. How to use it?

TestTimeProvider timeProvider = new TestTimeProvider();

ResetPasswordService service = new ResetPasswordService(testRepository, mockedEmailSender, timeProvider);

@Test

void should_throw_exception_when_token_is_expired() {

// given

var newPass = new Password("some-password-123$%^");

// and

service.sendToken(userId);

// and

var token = mockedEmailSender.getTokenFromEmail(userId);

// when

timeProvider.elapse(100, DAYS);

// then

assertThrown(TokenExpiredException::class, () -> service.resetPassword(userId, token, newPass));

}

See? We can simulate the passage of time by calling timeProvider.elapse(100, DAYS); and peek current instant during the test by calling timeProvider.instant(). It’s why we created a seemingly useless interface.

I hope you will add the TimeProvider to your next project, happy testing!